A good friend of mine attended a Gaelscoil on the north side of Dublin as a kid where he was fondly known to his teacher as The Préachán, or The Crow, for us non-fluent Irish speakers.

The nickname may in some small part be down to his quiet watchfulness or his quick intelligence, or even his hair, as black as the feathers of a wild bird. But more than likely it was down to his attempts to take flight from the school whenever he happened upon an open window.

His clós was the chatter of Irish-speaking children, tin whistles and fiddle-playing in the halla and carols as Gaelige in the local shopping centre at Christmas time. I loved to hear stories about this hub of Irish culture in the heart of Ballymun, a town that might seem so culturally different to most people’s idea of what Irishness is supposed to be.

My own school was similar to many others when it came to the Irish language. Old projector slides about blackberry picking. The monotonous repetition of tenses or an introduction of the odd “íocht” at the end of a word when stuck: “Sorry, Sir, Ní clue-íocht agam!”’

Perhaps if Úna-Minh Kavanagh had been around in my day things would have been different. Here is a woman who streams video-game commentaries in the Irish language and translates the kind of banter you’d most likely hear down the local.

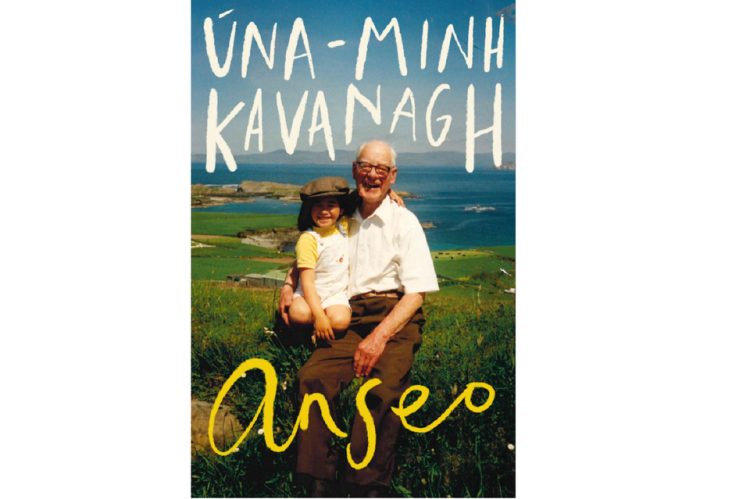

Her book Anseo might be an autobiographical account of her adoption in Vietnam, her upbringing in Kerry and her move to Dublin to study in Dublin City University – “swapping wellies for boots and acquiring Penney’s finest … like prepping for Paisean Faisean” – but it’s also an authentic celebration of the Irish language.

Scattered phrases surprise on every page. We learn some differences in the various dialects. There’s plenty of useful advice on how a person might bring Irish into their daily life, as well as a brief history of Dinneen’s Irish-English Dictionary. To those who argue against the relevancy of Irish and particularly those who claim it is too difficult to learn, she makes the point that on average, primary school kids participate in the Irish language about 117 hours per year and most of that involves memorising.

In the grand scheme of things, learning a language with so little immersion probably equates to attempting to train as a doctor by reading posters in dentist waiting rooms and browsing the odd copy of The Lancet.

In the background to this story of modern Ireland, the gaming and online freelance work, streaming and blogging, is the memory of Úna-Minh’s grandfather Paddy Kavanagh, the “famous storyteller and retired Garda” who cycled a black bicycle for most of his life and was immensely proud of Kerry GAA and Munster Irish (Gaelainn na Mumhan). This was the man who would introduce and inspire Úna-Minh’s love for the Irish language.

No doubt, she inherited the gift of story-telling from her grandfather, and this is where the book so often shines; her description of people and places, the holiday in Baile an Fheirtéaraigh, the stay in a home that so many of us can relate to, a picture of US president John F. Kennedy on the wall, the Sacred Heart and a shower that sprays horizontally as opposed to vertically.

She tells us of the stretches of sand in Béal Bán where her great-grandad fished and where her grandfather raced his currach. Each and every story in the book is connected to family and Irish culture and of course, the Irish language.

Natural and funny, there’s often mischief in her voice and courage in her ambition, the same bravery she has needed in the past when standing up to racism in this country. We hear of one such event on Parnell Street when a group of teenagers verbally abused her before one spat in her face. The attack and the consequent disregard from others at the scene would encourage her to turn to social media to share the experience.

Her story trended both nationally and internationally and launched her into the world of social activism. Of course, she has faced backlash, trolls hiding in their caves, only too happy (are they ever happy?) to list the reasons they believe Úna-Minh Kavanagh is not Irish.

Who’s that clip-clopping over my bridge?

Perhaps these people believe there exists some barometer of Irishnicity – a list of credentials that make one person that bit more Irish than the next. Presumably there’s some fiery hair in the mix, freckles too, a claim to a relative who once kicked an English landlord up the arse at a time when serfdom was in vogue and a goat called Páidí was high king of Ireland.

Sitting on top of that list always seems to be skin colour, the sure belief that a person can’t be considered Irish unless they have white skin.

Maybe the people of this country have been cultivating this type of discrimination for eons. Are we not skilled at perpetuating the stereotype, boxing towns into shallow clichés and forcing the people from those towns into their little boxes – the north-sider and the south-sider, the culchie and the townie, the blow-ins and the foreigner, and of course, the Traveller, a community who have known deep racism and exclusion only too well for decades.

Perhaps there’s a belief that, after a time, Ireland’s growing multiculturalism will naturally settle and racist ideas will wither away without effort. But look at our closest neighbour, with its arguably longer history of immigration, and the racism that continues to rear its ugly head there.

Over here, in an age when some media outlets are only to happy to carry the anti-Traveller rhetoric that some wannabe and sitting politicians spout, and where a family in an advertisement are inundated with hate messages just because of skin colour, it’s time to ask some serious questions about ourselves, where we are, and where we might be heading. And we had better find answers quickly.

If anything, Anseo pushes us all to interrogate and challenge what it means to be Irish. Is it accent or tradition or sense of humour? Is it history? The awareness of it. The unwillingness to let go. Was your idea of Irish formed in Hollywood California or Hollywood County Wicklow?

Is Irish something you embrace? Or is it something you are born into? Is it in the obtaining of an Irish passport or Irish citizenship? If an individual considers themselves to be Irish, should that not be enough? Or to turn it around, why should we demand that people be Irish to confer on them rights and dignity?

Around 12,000 years ago, a tiny birch seed was carried to Ireland on the breeze. How long did the roots have to be in Irish soil before it was considered to be a native?

Anseo is an account from one of the many voices of modern Ireland. As the title suggests, there’s no debating that Úna-Minh Kavanagh is here and accounted for. And this hardworking, proud Kerry woman is part of a growing landscape that is changing this country for the better.

Great review Daniel. That one’s definitely on the reading list!

Thanks Níall…hope you and the lovely family are great amigo !

Lovely review Dan. Thought provoking and ever relevant.

Thanks Sam, much appreciated. Hope you are keeping really well.

Lovely thoughtful review, and social commentary. Looking forward to reading Una-Minh’s book.